Part one of an essay by local artist Rich Gutierrez on the rejection of white supremacy throughout the nation’s past, linking struggles not only at home but internationally and stepping up to resist again and again.

Acquisition.

How did we get to “here?” It’s safe to say maybe we

never left “here.” They are swarming and they’ve been swarming; we just lied

when we said “never again.”

A couple of years ago I was in Munich, Germany, and

I wrote:

There has been an uprising in the fascist community here and Munich is

somewhat conservative compared to other places in Germany so it’s even worse.

Conservative groups claiming to not be fascists but accepting Nazis to be a

part of their groups have been demonstrating every Monday for a while and

ANTIFA and others come out to counter their demonstrations. Cops come out every

time, so it’s apparently very sketchy.

To read it

now and reflect on our current state is jarring. I wasn’t making the

connection, but why wasn’t I? These problems are a world away, I thought, they

will never reach us. These are things I’m sure passed my window, but the world

has shrunk. The impact of international opinion on the

attitudes of Americans has always affected our political climate more than we

imagine. I feel that the concern should have been placed more so on ones who

think themselves white. Far too often it’s placed on the backs all the

marginalized people of the U.S. That international disdain for our “inaction”

really aided in warping the self-image of Black and Brown Americans. I’m not

saying international opinion is solely to blame, I just see now that Trump is

in office everyone’s attitude has changed to refocus their critiques or maybe

should be refocused on their home. Globalization no longer allows these

uprisings to be considered isolated. We are all complicit.

We all must do our part to upset the beast.

In 1964 Harold Isaacs wrote that “the

end of white supremacy in the United States is being forced by the end of white

supremacy in the rest of the world.” With this in mind, we can see that it’s no

coincidence what was coming: with fascism en vogue worldwide it has empowered

the Nazis (alt-right).

It’s also important to acknowledge that we were

dismantling before and somehow we were subdued. I’d like to think we were

calmed by the illusion of victory, but white supremacy does a great job of

training others to defend it, even when it’s destroying them. The

disease convinces the host to eat itself. We ran them down before and we can do

it again, but now we will need to review the past to see where we zigged when

we should have zagged.

It’s the fear that raises their armour, that fear of

losing white privilege. As Toni Morrison said in a recent essay, “there are ‘people of color’

everywhere, threatening to erase this long-understood definition of America.

And what then? Another black President? A predominantly black Senate? Three

black Supreme Court Justices? The threat is frightening.” she goes on to say

that “white people’s conviction of their natural superiority is being lost.”

Black folks looked internationally for some type of hope

in liberation as the clock was turning to the 1930s. We looked in the direction

of some nonviolent resistances like the ones being used in India, working to

challenge British imperialism. Seeing other tactics in fighting imperialism

worldwide was where we found ways to liberate ourselves, ways to strengthen

ourselves. Using these examples, we thought maybe nonviolent resistances could

be used to oppose U.S. based white supremacy. We fought racism before race,

seeing the similarities in our struggles internationally, because racism is a

mechanism created by imperialism. In the mid-1920s, the Ku Klux Klan had

between two and three million members! Racial violence was overflowing and

omnipresent. Resistance did not seem like an option.

In an interview with Jimmy Carter held in the early 1980s,

he talked about the 1938 fight between heavyweight boxer Joe Louis ‘The Brown

Bomber’ and the German Max Schmeling. It was the rematch where Joe was

attempting to avenge his previous loss to Max, who had been highly celebrated

by the Nazis. He said the night of the fight his family ran the radio in the

fields. Many Black folks flocked to the Carters’ yard to listen to the fight.

As the Brown Bomber pummeled Schmeling, Carter recognized the quiet

satisfaction of the Black crowd. It was a jarring glimpse that he saw behind

that veil of Black humble submission with segregation. Behind it, a racial

pride resided and an intention to in any way possible stop oneself from

acknowledging the legitimacy of white supremacy. I see this now with Colin

Kaepernick and other sports stars more blatantly, but still the same. This

rejection of white supremacy at home and internationally is what empowers us.

The international pressure during the 1960s, which was

turning its focus on racial discrimination in the South, was enough to

encourage change, even if just to save face within our government. This small

change was — let’s be real —mostly a facade.

Our current government, for example, has done a good job of skewering anyone

who disagrees with them, manifesting these dissenters to the population as an

evil enemy who we should silence, instead of listening to their accusations

with concern. Another factor is that pressures internationally about civil

rights have lessened because internationally fascism is rising. Without it

Brexit could not have happened and the ‘refugee crisis’ in Europe could not be

used as an example of what may happen here with fear tactics.

Lynn Burnett wrote this in a piece about the global

context of the civil rights movement: “Although the United States had indeed

made remarkable progress, racial conflict showed no signs of ceasing after the

Civil Rights Act. In fact, the civil rights movement spread dramatically

outside of the South in the second half of the 1960s. As race-based poverty

continued to increase during the civil rights movement, the movement became

more militant. Riots flared across America’s cities, and it became increasingly

clear that white American racism was not just a southern problem. Despite these

facts, the world had become less critical… not of American racism, but of the

American government that they built relations with. Meanwhile,

by the time the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, U.S. officials had begun

to feel that Communism was much less of a threat. The continuing racial

oppression at home no longer seemed to pose much of a national security

concern. And so, just as the civil rights movement was turning its attention

towards the kinds of race-based poverty that plagues America to this day, one

of the major pressures in pushing forward racial justice in the United States — the international

pressures — began to fade.”

The power they/white supremacists/alt-right/fascists

hold comes from this structure of disembodiment; it’s been deployed in

different steps. In order for them (the

minority) to hold power over us (the majority), they have to create an

environment where we feel that we have no effect. It started early and

continued on in various forms.

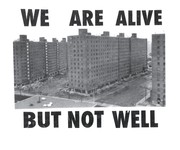

Take housing projects for example, which enforce rules

that corner majority black and brown people into housing that is built to

purposefully disenfranchise us. Children of the hood or low-income homes are

born beneath a doom cloud, as they say. Raised in poverty, pushed up against

violence and held down by crime, the world brands us with an enduring mark of

inferiority. This type of emotional scarring sometimes never heals.

Low-income housing is always a thinly veiled attempt to

house as many impoverished people as cheaply as possible. White Flight built

new roads that were used as distinguishing lines between these communities. The

ways these roads were constructed was purposeful; their appearance was

intentional to remind these communities’ inhabitants that they were helpless

and second-class or less. Detached from the rest of society in our own cultural

vacuum, our failure is almost unavoidable.

End part I

Source: The Crushing Sense of Nobodiness | Silicon Valley De-Bug