Measuring the Human Dimensions of Friendship

From the January 23, 2017, issue of THE WEEKLY STANDARD.

Although I’m hardly a fashionista, the exercise with my clothing made me feel solid, for reasons Alexander Nehamas helps explain in On Friendship, a response to a famous essay by Montaigne. Nehamas, who teaches philosophy and comparative literature at Princeton, argues that our friendships make us distinctive. He also says that modern friendship is mostly about taste.

Sorry, you’ve reached the limit on the articles you can view.

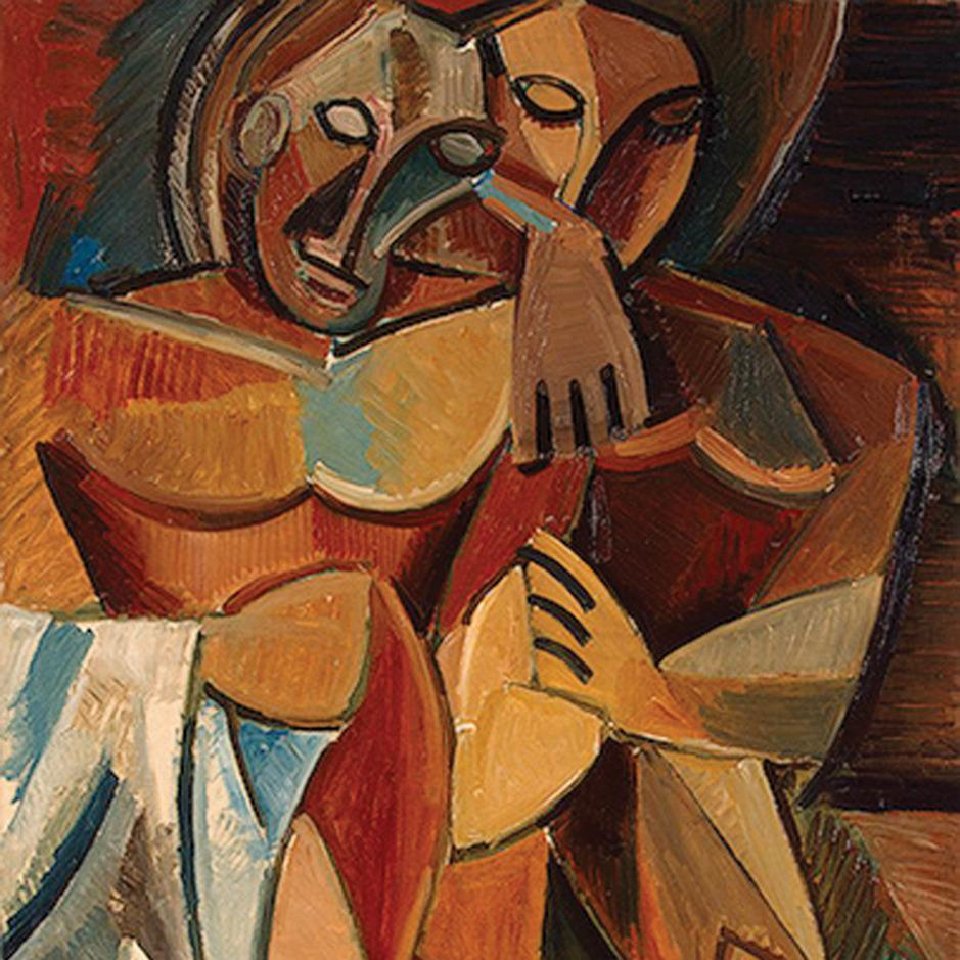

‘Friendship’ (1908) by Pablo Picasso

Nearly every year, I attend a Christmas service, even though I’m Jewish. Every year, the officiant delivering the homily points out that Christmas occurs in winter, bringing us hope in dark hours. As he says, “Perhaps it is the winter of your life.”

One of those “winter” years, this made me so sad I almost needed to run out. For comfort, I took the pendant of my necklace in my hand. It was a gift from a friend. And I found myself taking a kind of inventory: My dress had been suggested by another friend, while shopping, and my jacket was a hand-me-down. Of everything I wore that night, the only item I had chosen without influence was my underwear.

Although I’m hardly a fashionista, the exercise with my clothing made me feel solid, for reasons Alexander Nehamas helps explain in On Friendship, a response to a famous essay by Montaigne. Nehamas, who teaches philosophy and comparative literature at Princeton, argues that our friendships make us distinctive. He also says that modern friendship is mostly about taste.

By this logic, taste defines us. I disagree—despite my experience at All Souls and the rise of social media, clusters about taste. Loyal friends may be more important than ever in a world of unstable jobs, marriages, families and organizations. Although Nehamas gives us a lovely insightful appreciation of friends, his emphasis on aesthetics leaves out ethics. He leaves out character, dare I say virtue.

Our culture understands that friendship provides essential nutrients, and yet, like vegetables, considers it a side dish for most of adult life. Family, work, or romance should be more important by a certain age, or you’re immature. There also have been dark times when, as far as we know, Nehamas says, friendship was rare, private, and restricted to aristocrats. But philosophers and artists have always considered friendship to be the most significant relationship, with the essential clause that your friends be trustworthy.

Nehamas combines an introductory lecture, including academic-style endnotes, with his own thoughts, likening the attraction between friends to appreciation of art. He begins with Aristotle, who divided philia into three kinds that still sound familiar: Some friends exchange favors; some are for fun; the highest kind of friendship is possible only among people who are good and admire each other’s virtues—sharing ethics, not necessarily tastes.

As Nehamas points out, however, in our lives, friendship seems to be more arbitrary, like taste. Virtuous people may not choose each other. Bad people can be true friends, he argues, and good people can treasure the friendship of bad people. Also, because friendship is selective, it cannot be the basis of political idealism, so it is meaningless, he says, to call everyone “comrade.” We call strangers “buddy” and “brother,” referring to an ethic of political equality or God-based universal love. Nehamas’s ideal friendship is more intimate, dangerous, and demanding.

It feeds us in the way that art does, which is why the experience of art can feel like spending time with a friend. The emphasis on art goes beyond liking the same music or books: Friends make each other through interaction, like sculptors modeling each other’s clay. Admirable people, he says, are coherent, able to make use of their faults, so that “it becomes evident how the constraint of a single taste govern[s] everything large and small.”

Given this all-encompassing purpose, nothing between friends is minor:

Our idle conversations and commonplace interactions . . . are in the end neither idle nor commonplace . . . we respond to them . . . as parts of a longer process . . . what friends say and do together ramifies through their entire being.

The ramifying continues for years, or decades. Just as new friends—like new romances—change you, old friends must as well. A friendship that no long-er makes you more individual and coherent loses that invigorating sense that you are enriching your shared future. Although you might meet for dinner, you’re not really friends. And when a friend cuts you off, you are “losing a self.”

I have felt all this, intensely: Losing a friend erased years and diminished me, a new friend enlarged me, friends old and new give me the strength to be “who I am.” I am glad and grateful to hear so much explained so well.

Yet On Friendship is also irritating and chilly. In his analogies to art, Nehamas glides over the most important questions:

The love of art preserves the most essential feature of the love between people: the exhilarating sense that things will go well with both of us, though in ways we can’t ever fully articulate, if they acquire a place in our life.

This is a moving, exciting view of art and love. But is exhilaration the most essential feature of the love between people? Art is static and doesn’t have feelings. Friends change. Does the author really mean that abandoning a friend who no longer exhilarates you is no different than taking down a painting? He spends many pages on a play called “Art,” in which the purchase of a trivial painting threatens to destroy an old friendship. One friend can’t bear the idea that the other values something he doesn’t. They sound very much like teenagers who switch among cliques. In fact, teens exemplify the kind of friendship Nehamas makes definitive. Lavender hair and holes in your earlobes make sense if you see yourself as a work of art under Nietzsche’s “constraint of a single taste.” Adolescents feel every exchange as identify-defining, opening up the future.

Adolescence is also the time when we learn that the act of being a friend presents plenty of challenges that can make us more virtuous. If you pick well, true friends also influence you for the better by example, and as Nehamas says, these lessons continue through life. When friends drift away or make their leaving clear, even as an adult I may feel judged, ethically. It is soothing (and perhaps accurate) to believe that lost friends moved on because I was no longer helping them to become the people they wanted to be—because I was different, not flawed—even if they had some justification in their minds. But I want to know.

Character counts, on both ends. I have also found that friends have wounded me in ways that were predictable and in midlife am learning to be less surprised. “Before friendship is formed, you must pass judgment.” Seneca once wrote, “Ponder for a long time whether you shall admit a given person to your friendship; but when you have decided to admit him, welcome him with all your heart and soul.”

Nehamas doesn’t seem engaged with the question of why people might, or might not, persist when a friendship is difficult. This isn’t a book of sociology, but I wish he had noted that work, marriages, and friendships all seem to go better in a community of friends. He doesn’t touch on the elevated importance of friendship for people who live and work alone.

There is no mention of loneliness.

His vision seems to fit our times. In modern life, with some freedom and cash, we define ourselves through our selections in a marketplace of cultures. Social media make the point dramatically, with online acquaintances curating our news feeds. We rightly complain that online friendship usually isn’t the real thing—or rather, the whole thing. The problem isn’t solely the medium: True friendship goes beyond taste.

The author is right, of course, that a friendship shouldn’t deteriorate into an obligation. A friend freely chooses to spend time with you, again and again—weathering nights when you’re dull, because you may brighten again.

Sitting in the All Souls service that night, I was grieving the loss of a context. Later that night, I thought of Auden’s words written on the eve of World War II:

[T]he error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

Universal love couldn’t reach me, and romance seemed far away, so I turned in my mind to my friends. We understand that friendship isn’t exclusive or required. Close friends fill, and expand, the space between the id and indifference. They free us from the “error.” They soften the craving.

Temma Ehrenfeld is a writer in New York.

Web Link: http://www.weeklystandard.com/article/2006373

Next Page

The Weekly Standard

http://assets.weeklystandard.com.s3.amazonaws.com/tws15/images/logo-large.png

The Weekly Standard

2017

Washington, DC

Politics

2017-01-19

http://www.weeklystandard.com/measuring-the-human-dimensions-of-friendship/article/2006373

2017-01-19T08:45

2017-01-19T08:01

Measuring the Human Dimensions of Friendship

Nearly every year, I attend a Christmas service, even though I’m Jewish. Every year, the officiant delivering the homily points out that Christmas occurs in winter, bringing us hope in dark hours. As he says, Perhaps it is the winter of your life.

One of those winter years, this made me so sad I almost needed to run out. For comfort, I took the pendant of my necklace in my hand. It was a gift from a friend. And I found myself taking a kind of inventory: My dress had been suggested by another friend, while shopping, and my jacket was a hand-me-down. Of everything I wore that night, the only item I had chosen without influence was my underwear.

Although I’m hardly a fashionista, the exercise with my clothing made me feel solid, for reasons Alexander Nehamas helps explain in On Friendship, a response to a famous essay by Montaigne. Nehamas, who teaches philosophy and comparative literature at Princeton, argues that our friendships make us distinctive. He also says that modern friendship is mostly about taste.

Books and Arts, Temma Ehrenfeld, Art, magazine_repost

http://cdn.weeklystandard.biz/cache/280×280-4b5f3f722da4867b70d0ec20a5c35587.jpg

http://cdn.weeklystandard.biz/cache/280×280-4b5f3f722da4867b70d0ec20a5c35587.jpg

280280

Measuring the Human Dimensions of Friendship | The Weekly Standard.

Source: Measuring the Human Dimensions of Friendship | The Weekly Standard